UCF lab cutting through the dark of night with color night vision

UCF researchers improving night vision technology

Researchers at the University of Central Florida are working on a new technology that enhances traditional night vision devices by adding layers of color. The team at the UCF NanoScience Technology Center has created a system that dips further into the infrared light spectrum to decipher different light signatures.

ORLANDO, Fla. - The days of law enforcement officers trying to spot the bad guy on black and white or splotchy green night vision may soon be cleared up in color thanks to scientists at the University of Central Florida.

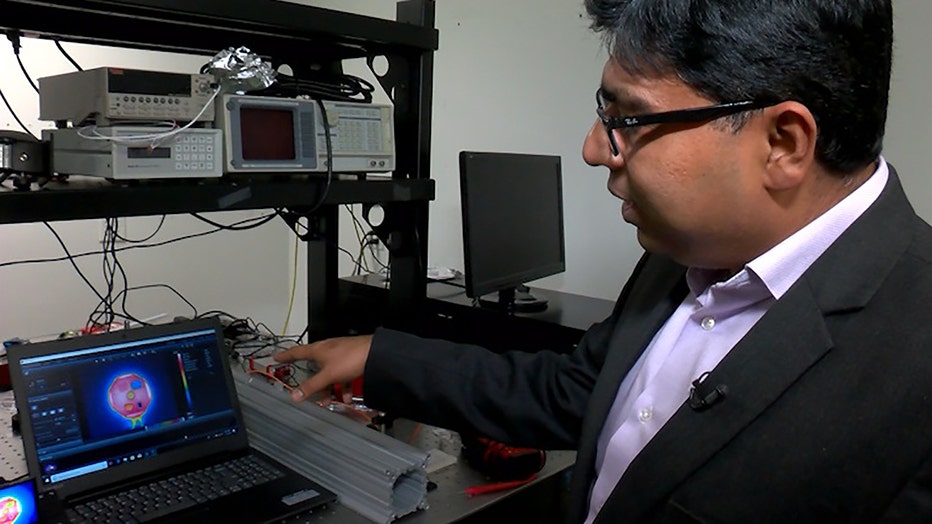

Dr. Debashis Chanda and a team of about five have developed the new night vision technology for the U.S. Department of Defense (DOD). Their team at the UCF NanoScience Technology Center has created a system that dips further into the infrared light spectrum to decipher different light signatures. So rather than just see in black and white or shades of green, the cameras can assign different colors to different things on the screen.

In the team’s laboratory, they fabricated different types of metals onto a small disk. In the darkness, like anything else, you couldn’t see anything, but under the new camera the metals all showed up a different color. Chanda said the real-world applications could be much more interesting though.

“For instance, if you’re looking at a human being in the night, you can actually not only look at his thermal signature from the outside of their body, but you can also look into, say he or she may have a phone in their pocket,” said Dr. Chanda.

Another example may be soldiers trying to enter an enemy strong-hold under the cover of night. Chanda said the technology would potentially let them see if a person lurking up ahead had a weapon on them or some other dangerous object. However, while the DOD is first in line for the technology, Chanda said it’s not just made for spotting weapons or zeroing in on "bad guys."

“Say you want to detect various gases,” said Dr. Chanda. “You want to detect, say pesticides from fruit and vegetables.

”He said it could also be used in discovering different gasses and objects in space exploration, deciphering issues in electrical systems, in-home security systems, or could be integrated into autonomous technology like self-driving vehicles. Infrared vision like this is out there, but Chanda said it’s always come with a major barrier: it needs extreme cold to function.

“Present infrared detectors actually need cryogenic cooling because you need a way to reduce the temperature to 321 degrees Fahrenheit to make it work,” said Chanda.

Not so with their new technology which can operate at room temperature; greatly expanding its potential uses.

“We’re working on improving the sensitivity to improve the performance,” he said.

However the team is hopeful their clearer, more colorful look into the night may be lighting up in the real world soon.